Poverty Solutions shares innovations, lessons learned in 2024

By Lauren Slagter

Poverty Solutions at the University of Michigan made significant strides in its action-based research to prevent and alleviate poverty in 2024, thanks to the interdisciplinary work of faculty, staff and students across the university.

Poverty Solutions released its annual impact report Jan. 31, underscoring takeaways from its efforts over the past year

Kristin Seefeldt

“We’re proud of the impactful work we’ve contributed to in Detroit and throughout Michigan,” said Kristin Seefeldt, acting faculty director of Poverty Solutions and an associate professor of social work in the School of Social Work, and associate professor of public policy in the Gerald R. Ford School of Public Policy.

“The innovations we’ve tested and the lessons we’ve learned have profound implications for broader anti-poverty initiatives across the United States. We’re excited to share what we’ve learned in this impact report,”

The report included information on the following key research areas:

- Innovations in cash transfers, via Rx Kids, the nation’s first citywide maternal and infant cash prescription program; and Guaranteed Income to Grow Ann Arbor, which takes a novel approach to providing guaranteed income to self-employed workers with low incomes.

- Promoting economic opportunity through community violence interventions and summer youth employment.

- Addressing the costs of housing instability with an assessment of Michigan’s housing inventory, examining the long-term costs of eviction filings, and making data on child and youth homelessness more accessible.

- Laying the foundation for reparations by quantifying historical harms to Detroit’s Black residents.

- Supporting participatory democracy by empowering voters to engage with candidates on poverty issues and amplifying public opinion polling on Detroiters’ priorities for elected officials.

Poverty Solutions is a universitywide presidential initiative that also supported faculty and students in 2024 and elevated the university’s profile as a leading poverty research institution, via the following milestones:

- Sustaining 22 active research projects.

- Contributing to 11 publications, including academic journal articles, action-oriented policy briefs, and working papers.

- Awarding $80,000 in seed grants to U-M faculty.

- Employing 56 student research assistants.

“At Poverty Solutions, we see strong alignment between our work and the priority impact areas for U-M’s Vision 2034 campaign,” Seefeldt said. “We look forward to continuing to serve the common good through our action-based research agenda, set in partnership with policymakers and community organizations working on the front lines of poverty alleviation.”

SchoolHouse Connection and University of Michigan’s Poverty Solutions Launch Comprehensive Data Profiles on Child and Youth Homelessness

WASHINGTON, D.C. — SchoolHouse Connection, in partnership with the University of Michigan’s Poverty Solutions initiative, today announced the launch of new, updated interactive data profiles examining child and youth homelessness across the United States. These profiles organize and analyze federal data over a four-year period.

“Child and youth homelessness is largely invisible in our communities and in our schools,” said Barbara Duffield, executive director of SchoolHouse Connection. “These data profiles help shine a light on these students, the harmful impact of homelessness on their school attendance and achievement, and where progress can be made.”

The interactive dashboard allows users to explore homelessness trends across multiple geographic areas – from national and state levels to local communities, U.S. Congressional districts, and state legislative districts. New features help school districts assess whether they may be under-identifying students experiencing homelessness and highlight districts that are categorized as “severely underfunded” – those that have identified students experiencing homelessness but do not receive McKinney-Vento subgrants to serve them. Users can also compare educational outcomes between homeless students and their housed peers through critical indicators such as chronic absenteeism and graduation rates.

Jennifer Erb-Downward

“The data profiles make information on children experiencing homelessness easily accessible to decision makers at local, state, and national levels,” said Jennifer Erb-Downward, director of housing stability programs and policy initiatives at Poverty Solutions at the University of Michigan. “This is the kind of information that is needed if we are going to come together to truly prevent and solve homelessness.”

Join Us for a Deep Dive into the Data

SchoolHouse Connection and Poverty Solutions will host a webinar today, January 29, at 12PM Eastern to demonstrate the features of the new data profiles and discuss key findings. Participants will learn how to:

- Navigate the interactive dashboard

- Interpret trends and patterns in the data

- Use this information to inform local and state policy

To register for the webinar, click here. The recording will be available here within 1-2 business days. The data profiles are now available at https://schoolhouseconnection.org/article/data-profiles

Q&A: Transportation insecurity in Detroit and beyond

Alexandra Murphy discusses why 36% of Detroiters have trouble getting where they need to go and how a new tool could guide better transportation solutions

Student-led civic design workshop reimagines Michigan eviction court forms

ANN ARBOR – Navigating the eviction process is a daunting challenge for many Michigan residents, especially for those without legal representation. Every year, between 170,000 and 190,000 eviction cases are filed in Michigan, affecting about 1 in 6 households, with only 2% being represented by an attorney.

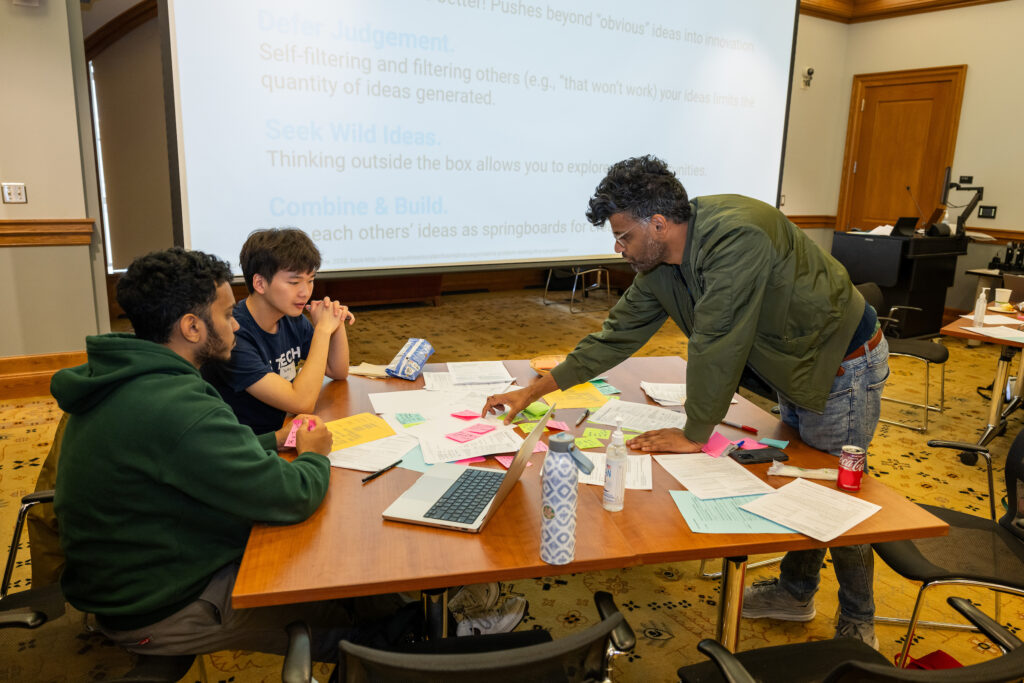

To help address this barrier, over 20 students, faculty, and legal professionals came together on Nov. 1 at the University of Michigan for a design workshop aimed at simplifying Michigan’s eviction court forms. The design workshop built on work completed by the School of Information’s Civic User Testing Group, which gathered feedback from Michigan residents on information and usability issues they encountered when understanding and completing Michigan landlord-tenant forms. U-M’s Poverty Solutions initiative and UMSI’s Engaged Learning Office were co-sponsors of the event and provided logistical support.

Civic design workshop organized by School of Information student on Nov. 1, 2024, redesigned Michigan eviction forms. (Michigan Photo)

The event was organized by School of Information master’s student Rachael Zuppke, with support from faculty members Scott TenBrink and Rhea Acharya. Zuppke, who has a background in Michigan’s nonprofit and legal aid sectors, saw the workshop as an opportunity for students and community partners to collaboratively tackle the complexities that tenants face in eviction proceedings.

“I spent years helping people navigate the eviction process. It is a complicated and fast-paced system and most tenants do not have the resources or help they need to understand the web of information and processes involved,” Zuppke said. “I set up this workshop so that student designers and community partners could work together to re-envision Michigan’s eviction forms, integrating feedback from Michigan residents, with the goal of making forms clear and actionable for those without legal training.”

Civic design workshop organized by School of Information student on Nov. 1, 2024, redesigned Michigan eviction forms. (Michigan Photo)

Attendees included representatives from the legal aid community who shared insights based on their experiences working directly with tenants. Nora Ryan, director of Michigan Legal Help, described the event as “exactly the sort of innovative event we need to help break down barriers to justice and make our courts more accessible to the community.”

The workshop’s collaborative approach reflects a growing commitment within Michigan’s legal and educational communities to make the justice system more user-friendly and accessible for all.

Article by Rachael Zuppke. Video by Trevor Bechtel and Qiying Feng.

Experts, policymakers highlight new studies showing statewide Paid Family and Medical Leave would benefit workers, economy

Release courtesy of the Michigan League for Public Policy

Contact: Laura Ross, Communications Director, Michigan League for Public Policy

lauramr@mlpp.org

LANSING—On Wednesday, Nov. 13, advocates and experts held a virtual press conference highlighting the benefits that a statewide paid family and medical leave program would have for Michiganders and the importance of passing the Michigan Family Leave Optimal Coverage (MI-FLOC) during the final weeks of the 2024 legislative session.

“Today, we are here to discuss how the results of the qualitative studies confirm what we already know to be true,” said state Sen. Erika Geiss. “These studies highlight that paid family leave is a win-win for people and businesses. Companies with paid leave programs report higher employee retention, increased productivity and lower turnover costs. For workers, they will have the time and financial assurances that they can take care of themselves or a loved one, without sacrificing financial security. FLOC is also good for the economy. Paid leave programs lead to healthier, more productive workers, which translates to a stronger workforce and a more resilient economy, for generations to come.”

The MI-FLOC legislation introduced last year would establish a 15-week paid family and medical leave program in Michigan, which is something that the majority of Michiganders–71%–have said they support. The studies referenced in today’s press conference were released by Michigan’s Department of Labor and Economic Opportunity (LEO) and explore the health, employment and economic impacts of paid family and medical leave programs.

Luke Shaefer

H. Luke Shaefer, the director of the University of Michigan’s Poverty Solutions and a co-author of one of the reports, noted that there are many positive economic impacts that come out of paid leave policies, including better economic security for workers and the multiplier effect of those dollars cycling through local economies. He also noted that people who go on leave are more likely to stay in a job, resulting in a short-term loss for employers for a long-term gain, and that paid leave programs can have a positive impact on labor force participation for those most likely to need to take leave.

“When we look, for example, at the labor force participation of women in other countries that have much, much more generous paid family leave policies than in the United States, we see that women in those countries have higher labor force participation over the long term as well as in all of the other states that have adopted a policy like this,” Shaefer said.

Monique Stanton, president and CEO of the Michigan League for Public Policy, also touched on how an actuarial analysis also released by LEO this year shows that paid leave is a low-cost, high-value program for workers and businesses.

“Paid leave will cost less than a pop or a cup of coffee each week for workers that make the minimum or median wage. And, for that low cost, it will provide workers with the security they need to keep their jobs and the majority of their income if they were to need to take an extended leave from work to care for themself, a loved one or a new child,” Stanton said. “The costs of not implementing paid leave include wage and job losses for workers and families, worse health outcomes, higher healthcare costs, talent losses for businesses, and a negative impact on the state economy.”

Thirteen states and the District of Columbia have passed and enacted paid leave policies.

“It’s time for Michigan to join California, Colorado, Connecticut, Delaware, Hawaii, Maine, Massachusetts, Minnesota, New Jersey, New York, Oregon, Rhode Island and Washington—the 13 states that have paid leave programs,” said Mothering Justice National Executive Director and Founder Danielle Atkinson. “What we have an opportunity to do here in Michigan is to stand up for people who have called for this policy overwhelmingly. We know this policy is overwhelmingly popular because it’s overwhelmingly needed.”

According to estimates, if Michigan were to implement the most robust plan included in the actuarial analysis commissioned by the State of Michigan, a worker making the state median wage ($46,940 at 40 hours per week) can expect to pay $178.37 annually or a little more than $3 per week in contributions. And an individual earning the current minimum wage ($21,486.40 at 40 hours per week) can expect to pay $81.65 annually or about $1.50 per week.

The studies referenced in yesterday’s press conference are:

- Economic and Health Impacts of Paid Parental, Caregiving, and Medical Leave by Karen Kling, H. Luke Shaefer and Betsey Stevenson with the University of Michigan’s Poverty Solutions

- Paid Family Medical Leave: Health & Employment Outcomes by Patricia Stoddard-Dare, PhD

Poverty Solutions to support new NIH health equity research hub at U-M

With the goal of building the science that can strengthen efforts to reverse health disparities—which keep millions of Americans in poorer health due to lack of access to food, health care and other needs—the University of Michigan will receive $6.75 million from the National Institutes of Health to establish a health equity research hub.

U-M is one of five institutions sharing in $37 million in funding from the NIH’s Common Fund to operate ComPASS Health Equity Research Hubs.

The hubs, according to the NIH, will provide “hands-on research” and “technical scientific support rooted in health disparities expertise necessary for successful community-led research projects.” Each institution’s hub supports the NIH’s 25 Community-Led Health Equity Structural Interventions Projects.

U-M’s hub will be led by the School of Public Health and directed by Justin Heinze and Roshanak Mehdipanah, both associate professors of health behavior and health equity and faculty leads at U-M’s Prevention Research Collaborative.

“The University of Michigan’s School of Public Health has been a leader in multidisciplinary research and the hub will be no exception,” Mehdipanah said. “It will bring together a multidisciplinary team of researchers and community practitioners with extensive experience in applied community-based participatory research, practice and policy focused on addressing structural determinants of health with an equity lens.”

U-M’s hub will involve 17 researchers from a dozen schools and colleges across campus, including the School of Nursing and Taubman College of Architecture and Urban Planning. The hub’s community-led research projects will focus on health inequities such as health care access, food access and the built environment. U-M’s Michigan Institute for Clinical Research and Poverty Solutions initiative will be key partners in the hub.

“This is such an exciting NIH initiative to fund communities directly, which in turn leverage their local knowledge and resources to address systemic public health problems facing their areas,” Heinze said. “Our job as a hub is to be a centralized research resource for them, providing tailored scientific, technical and collaborative support to support the interventions happening in those communities,” Heinze said.

NIH also selected New York University Grossman School of Medicine; University of Maryland, Baltimore; University of Mississippi Medical Center; and Yale University as ComPASS hubs.

ComPASS, which stands for Community Partnerships to Advance Science for Society, is an NIH program designed for “community-based organizations to lead the way in researching, designing, implementing and assessing projects that address community needs and reduce health disparities.”

The ComPASS program is managed collaboratively by NIH staff from the Common Fund; National Cancer Institute; National Institute of Mental Health; National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities; National Institute of Nursing Research; National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; and NIH Office of Research on Women’s Health. Other NIH institutes, centers and offices participate in program development and

Management.

U-M’s Grant number: 1UC2CA293569-01

Survey shows Detroiters’ top priorities for city officials going into election

DETROIT—Crime and safety tops the list of priority issues that Detroit residents want to see city officials address going into the November 2024 election, according to a survey conducted by the University of Michigan in partnership with Outlier Media.

Thirty-nine percent of Detroiters said crime and safety are among the two most important issues they want the city of Detroit to address. The survey—fielded in April by U-M’s Detroit Metro Area Communities Study—asked open-ended questions, so people could answer in their own words. Other top priorities included:

-

Road repairs (17%)

-

Neighborhood maintenance (16%)

-

Structural blight (15%)

-

Housing affordability (15%)

People who highlighted crime and safety referenced the need for “lower crime rate,” “safer community to live and explore,” and “safe parks for the kids.” Related to crime and safety, another 4% of Detroiters said improving the quality of policing should be a top priority for local elected officials. Comments on policing included the need for more police visibility in neighborhoods and the need for police reform and de-escalation training.

Mara Ostfeld

“Safety is clearly a priority for Detroiters, and they’re thinking about it in a variety of ways,” said Mara Ostfeld, faculty lead for DMACS and co-author of a new brief on the survey findings. “While there is a lot of attention on the presidential election and other national races, what’s happening in someone’s community tends to be a stronger motivator to vote. Voters want to see policies that shape their day-to-day experiences.”

DMACS has released a series of briefs supported by U-M’s Poverty Solutions that explore topics relevant to the 2024 election, including Detroiters’ intentions to vote, the top issues Detroiters would like to see federal elected officials address, and views on legal immigration held by residents in four Michigan metro areas.

Analysis of survey responses from a representative sample of 1,100 Detroit residents found Black Detroiters (43%) were more likely to list crime and safety as a top priority for city government than white (26%) or Latino (21%) Detroiters. Latino Detroiters were more likely to list road repairs as a top priority for the city (33%) than Black Detroiters (18%) and white Detroiters (6%). Among white Detroiters, transportation, schools and taxes were more likely to be listed as top priorities for city government than among Black and Latino Detroiters.

Yucheng Fan

“There were limited differences in priorities for local government between income groups, with all income groups citing concerns about crime and safety,” said Yucheng Fan, data manager for DMACS and co-author of the brief on priorities for city government. “Housing affordability was more likely to be listed as a top priority for the city government among households with lower incomes. Higher-income households were more concerned about taxes.”

Priorities differed for residents of different parts of the city. Concerns about crime were most pronounced in City Council District 1 in northwest Detroit, where the city is supporting two community-led violence intervention efforts through the ShotStoppers program.

In City Council District 7 on the west side of Detroit, neighborhood maintenance was most frequently mentioned as a top priority for the city to address. Road repairs topped the list of priorities for residents in City Council District 1 in northwest Detroit, City Council District 4 in east Detroit; and City Council District 6 in southwest Detroit. Housing affordability was listed as a top priority in City Council District 3 in east Detroit and City Council District 5, which includes much of downtown Detroit.

Kristin Seefeldt named acting director of Poverty Solutions at U-M

ANN ARBOR – Kristin Seefeldt has been named acting faculty director of Poverty Solutions at the University of Michigan for the 2024-25 academic year while inaugural faculty director Luke Shaefer is on sabbatical.

Seefeldt, who has served as associate faculty director of Poverty Solutions since 2019, has established a national reputation for her contributions to U-M’s poverty research agenda over the past three decades. She was a researcher on a number of U-M studies of welfare reform conducted during the late 1990s and early 2000s. From 2004 to 2010, she was assistant director of the National Poverty Center, when U-M hosted the federally-funded research center that preceded Poverty Solutions, which launched as a presidential initiative in 2016.

An associate professor of social work and public policy, Seefeldt holds an MPP and a PhD in sociology and public policy from U-M. Seefeldt is the principal investigator administering and studying Guaranteed Income to Grow Ann Arbor (GIG A2), an innovative guaranteed income pilot providing monthly payments of $528 to 100 low-income entrepreneurs and gig workers in Ann Arbor in 2024 and 2025. She also is part of the research team for the Community Tech Workers program in Detroit. Seefeldt’s overall research agenda is focused on how policy and economic changes affect people’s everyday lives.

Valeria Bertacco

“I am enthusiastic about the future outlook of the Poverty Solution initiative, and I am looking forward to working with Professor Seefeldt as its acting director. Her professional track record places her in a unique position to lead this initiative to new levels of growth and engagement,” said Valeria Bertacco, vice provost for Engaged Learning at U-M, which oversees Poverty Solutions.

Seefeldt steps in for Shaefer, who founded Poverty Solutions in 2016 and established its focus on action-based research, done in partnership with policymakers and community groups, to find new ways to prevent and alleviate poverty. Under Shaefer’s leadership, Poverty Solutions:

- Established a Detroit Partnership on Economic Mobility with the Detroit Mayor’s Office and Detroit community-based organizations to set an economic mobility agenda for the city;

- Informed the design of the 2021 expanded Child Tax Credit, which contributed to a record-low child poverty rate; and

- Partnered with Michigan State University to launch a first-of-its-kind citywide maternal cash assistance program in Flint called Rx Kids, which provides payments to people during pregnancy and the first year of the child’s life.

During his sabbatical, Shaefer will continue his role as principal investigator for Rx Kids, which recently received $20 million from Michigan’s Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) funds to expand to other communities across the state.

Julia Weinert

“Dr. Shaefer has done an incredible job of setting the initiative up for success prior to his sabbatical. I’m excited to work more closely with Dr. Seefeldt over the year ahead to leverage her unique experience and expertise to carry out our mission,” said Julia Weinert, managing director of Poverty Solutions.

In this Q&A, Seefeldt shares more about her vision for Poverty Solutions this year and the ways campus units and community partners can get involved in advancing efforts to prevent and alleviate poverty.

You’ve been contributing to poverty research at U-M for three decades. What makes the current iteration of Poverty Solutions unique in its approach to poverty scholarship?

Seefeldt: U-M has long been known for its pioneering research on issues affecting people with low incomes. For example, the Panel Study of Income Dynamics (PSID), launched at the Institute for Social Research in the 1960s and continuing today, is an important dataset for understanding families’ economic well-being. The work I did with Sheldon and Sandra Danziger and former Ford School Dean Rebecca Blank provided key insights into the effects of a very major policy change – welfare reform – on families with low incomes. All of this work was definitely policy relevant, and U-M poverty researchers have always looked for opportunities to inform policymakers about our work, but the work was usually researcher-driven, based on questions we found interesting and worthwhile to pursue. And, the primary product was often a book or journal article, both of which have great value but are often inaccessible to those outside of academia.

Poverty Solutions, though, uses a community-driven approach in generating the topics and issues that we study. We work collaboratively with community partners and policymakers to identify the questions that need answering. We also look for ways to make changes to policies and systems – that is the central goal of our work.

What projects are you most excited about for the coming academic year?

Seefeldt: I’m excited to continue working on the GIG A2 research. Last year we were really focused on getting the pilot up and running. Now we have the opportunity to dig into the data we’ve collected, both from surveys and interviews, to learn more about the program participants, the issues affecting their lives, and the ways they use their guaranteed income payments.

I’m also excited to get to know more about the projects in which I haven’t been as deeply involved and learning from our staff.

How can people get involved in supporting Poverty Solutions’ work?

Seefeldt: Our communications team does an excellent job at keeping our website, poverty.umich.edu, up to date with the latest news related to our work. People can also join the list to receive newsletters. Every fall we host a speakers series on campus, featuring leaders in the field who are doing innovative work. Those talks begin on Sept. 27, running every Friday through Nov. 8. If you can’t attend in person, a livestream will be available.

If you have an idea about a possible collaboration, whether on campus or in the community, reach out to povertysolutions@umich.edu. We’d love to talk with you!

Racial and gender bias in US crime victim compensation programs highlighted in U-M report

Contact: Katrina Hamann, kbham@umich.edu

Significant racial and gender disparities exist in U.S. crime victim compensation programs, revealing Black and Indigenous people as well as survivors of gender-based violence face unique challenges in obtaining financial support, according to a new report from the University of Michigan.

Despite intentions to alleviate the financial burden for crime victims, eligibility restrictions based on perceptions of innocence and cooperation with law enforcement disproportionately exclude these groups.

“Over the last several years, we have learned more and more about implicit and explicit bias in policing,” said Jeremy Levine, U-M associate professor of organizational studies. “Relying on the police to determine victim eligibility imports all those biases into the provision of public benefits, which disadvantages victims of color in ways comparable to other inequalities in the criminal justice system.”

Levine authored the report, Inequality in Crime Victim Compensation, from U-M’s Center for Racial Justice and Poverty Solutions.

Crime victim compensation is a public benefit intended to cover financial costs associated with crime. Victim compensation benefits can be used to cover medical bills, counseling, relocation, funerals, crime scene cleanup and other related expenses after insurance and welfare benefits are accounted for. Such programs are managed by states with up to 75% of program costs paid for by a federal subsidy.

Key findings show police discretion plays a pivotal role in determining victim eligibility, with subjective criteria, such as perceived misconduct or failure to cooperate, leading to biased outcomes.

Black and Indigenous victims, especially Black men, are significantly less likely to receive compensation than victims from other social groups. In addition, women survivors of domestic violence, sexual assault, stalking and human trafficking are less likely than victims of other crimes to be compensated.

“These eligibility requirements were created to incentivize victim cooperation with law enforcement,” Levine said. “But in the end, all they accomplish is punishing victims after their victimization while also failing to work as an incentive to cooperate.”

The report calls for urgent reforms, including:

- Removing racialized and gendered barriers to compensation, such as cooperation with law enforcement and misconduct criteria.

- Expanding alternative procedures for proving victim status and using medical or social service documentation rather than relying on police assessments.

The analysis, based on data from 18 states, points to ongoing legislative efforts in states like Illinois and New York that have successfully reformed their victim compensation criteria, significantly reducing denials and promoting greater equity.

Studies look at health, employment impacts of guaranteed income programs

By Jeff Karoub

Michigan News

Guaranteed income programs don’t appear to improve the health of recipients, but they remain an important tool to consider for reducing poverty, according to research from the University of Michigan and others.

The findings come from research released by OpenResearch’s Unconditional Income Study, which gave 1,000 adults $1,000 per month for three years. The randomized controlled trial examined the effects of the cash transfers on recipients, including their overall health, employment outcomes and how they spent the money.

Sarah Miller

Leading the study on health effects was Sarah Miller, associate professor of business economics and public policy in the Stephen M. Ross School of Business. She said the cash generated only short-lived (one-year) improvements in stress and mental health, and no effect on physical health, as measured by self-reports.

Not seeing a longer-term reduction in stress was a disappointment, Miller said, since that could be one way that more income improves health.

“There’s so much energy in health policy now for addressing ‘social determinants of health’ — and poverty in particular,” said Miller, who also is an associate professor of health management and policy in the School of Public Health. “Could cash transfers be the way to meaningfully and effectively reduce health disparities? It’s hard for me to look at these results and say yes.”

However, Miller noted she and her colleagues found an overall increase in visits to hospitals and dentists. It’s possible the uptick in medical care could improve health over a longer time horizon.

Participants, who were mostly recruited by mail in a diverse set of counties in Texas and Illinois, were asked if they would be interested in a study in which they would receive at least $50 per month. Of the 14,000 respondents who consented, researchers drew a weighted random sample of 3,000 to ensure racial and income diversity.

All of those in the latter sample group were enrolled in a monthly cash transfer program of $50, and 1,000 of them were selected randomly to receive $1,000 a month. Researchers reasoned the control group should continue to receive the smaller amount so they would be more likely to participate in future surveys.

In the employment-related study, Miller and colleagues found that $1,000-per-month recipients worked roughly 1.4 fewer hours per week on average. She said she doesn’t view that as negative. Time away from work is something they value and she views that as a “reasonable thing to use the payment on.”

Not surprisingly, when it came to spending, the research also showed increased consumption of food, leisure, transportation and housing. The participants boosted their spending in those areas by roughly $300 a month.

While those expenditures didn’t appear to improve health, they did provide financial flexibility and freedom — “a feature of cash, not a bug,” said Miller, also a co-author on the employment and spending studies.

“If the policy goal is to improve health specifically, there are health-targeted interventions that we know work: make medical care cheaper, expand coverage, reduce barriers to initiating a primary-care relationship,” she said. “I am personally in favor of more cash transfers and think that the U.S. should do more to help alleviate poverty. It’s important to know what cash transfers can and can’t accomplish, though, so we can make good policy decisions.”