Employment and Access to Good Jobs in Bad Times: The case of Detroit

Download PDF of full policy brief

By Michael Evangelist, Lucie Kalousová, and Sarah Seelye

Introduction

The Great Recession, which extended from December 2007 through June 2009, was the worst recession to strike the United States since the Great Depression. It spurred large scale job losses, substantial increases in long-term unemployment, and greater perceived job insecurity among workers. With close ties to the auto industry and the financially troubled “Big Three” car companies, the Detroit area experienced higher rates of unemployment than the country as a whole during the economic downturn. In 2009, the unemployment rate for working-age adults in the three-county region encompassing the Detroit Metro Area averaged 15.3%, far surpassing the national average of 9.0% that year.

While the recession propelled job loss, even those who kept their jobs were not immune from the stressful effects of the economic downturn, as evidenced by reports of job insecurity. Workers in the Detroit area experienced high rates of perceived job insecurity following the Great Recession. Those who thought they were likely to lose their jobs reported worse physical and mental health than workers who expected to stay employed.

In addition to these employment problems amplified by the Great Recession, the share of “good jobs” in the U.S. has diminished over time and access has been limited to an increasingly select group. For example, “good jobs,” defined as those providing a median hourly wage, health insurance, and a retirement plan, are increasingly held by individuals with a college degree or more. While 43% of workers with a high school degree or less had a good job in 1979, by 2010 only 19% of these workers could claim such a job.

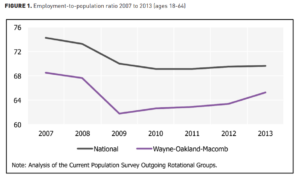

This brief examines how trends in employment, perceived job insecurity, and “good jobs” among workers in the Detroit Metro area changed in the years following the Great Recession. We observe some reassuring signs of recovery. For example, at the height of the recession in 2009, the employment-to-population ratio for Metro Detroit was more than eight percentage points lower than the national average. During the recovery period, the percentage of the population employed increased steadily for Metro Detroit, closing approximately half of the gap with the national average. Furthermore, while the share of workers who had a good job remained constant at 37%, those who reported job insecurity fell from 17% to 8% between 2009 and 2013. At the same time, we also find that inequalities in Metro Detroit continue to persist. As we discuss below, African Americans and those with less education continue to have less access to good jobs and report considerably more job insecurity compared to their counterparts. In this brief, we examine each of these employment conditions in greater depth.

Conclusion

At first glance, it appears that workers in the Detroit area have recovered their pre-recession employment levels and have nearly recovered with respect to some key job benefits. Close inspection of the more granular patterns hiding behind the encouraging trends, however, reveals social inequalities in who recovered that mirror those which existed before the Great Recession. While some groups of workers have recovered their sense of stability and attained high-quality jobs, the prospects for others have remained stagnant—or even worsened.

Notably, one group of Detroiters stands out as not enjoying benefits of recovery equal to the rest: workers with a high school degree or less. Although their sense of job security has greatly increased over time, their jobs provided fewer benefits at the end of the study than they did in the beginning. On every job benefit indicator we measured, workers with a high school degree or less experienced worse conditions. This retreat in job quality cannot be explained by the post-recession reappearance of the least desirable jobs that may have been eliminated during the Great Recession. Workers with a high school degree or less were overall less likely to be employed in 2013 than they were at the height of the downturn. Four years after the end of the Great Recession, this group of Detroit-area workers had lower participation in the labor force and, for those who worked, worse job conditions.

Our findings reflect national trends that point to the continued decline in the availability of high quality jobs, particularly for less-educated workers. Job growth in the years following the Great Recession was driven predominately by hiring in low-wage industries. During the early part of the recovery, real wages declined across occupations but the effect was most pronounced in the middle and bottom of the occupational wage distribution. The uneven economic recovery may have exacerbated long-term growth in labor market inequality. Previous evidence has reported that the economy has lost approximately one-third of its ability to create high-quality jobs since 1979, reducing the availability of good jobs even for college-educated workers. However, less-educated workers have fared the worst. With reductions in manufacturing and the growth of the service sector, substantially fewer workers with a high school degree or less are able to secure higher-paying jobs with quality benefits, as we have seen in Metro Detroit. Our results suggest that without policies aimed at improving employment opportunities, workers, and in particular less educated workers, will continue to face difficulty securing high-quality jobs that would provide recovery from the Great Recession and economic mobility for themselves and their families.